and monitoring tools and solutions.

This is both the good news and the bad news as the problem suddenly gets larger and harder!

The challenge is to choose the right tools and the right solutions unique and specific to your organization’s requirements.

Security Event Management, Generating Reports from Your System.

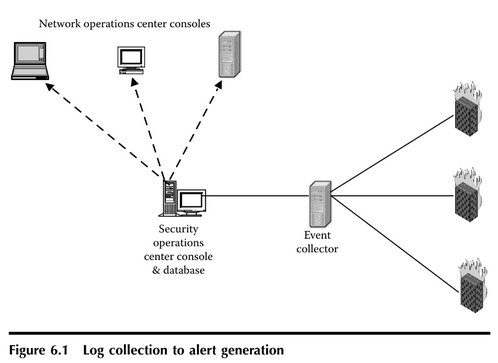

Network operations center consoles.

Security operations center console & database.

Event collector.

Log collection to alert generation burden on the system.

The output will look something like Figure 6.1, Detailed Records, the result of a drill-down, but would contain many more records as it would also include all activity from the previous 24 hours.

A few examples of this type of batch reporting may be the Failed Authentication report as indicated, but with more records because it covers a long span of time.

Other such reports could be the correlation report between your enterprise virus console and your IDS (intrusion detection system), whereby it produces a batch report identifying segments where signatures of malicious code were detected and segments where desktop virus eradications had occurred based on your enterprise virus console report.

The benefit of this batch reporting is that this can be a key threat mitigation report by providing the status of your enterprise and not requiring the subject matter experts to be constantly keeping watch.

The report can contain the detail down to the machines detected by the IDS, and the machines that had eradications occur from the virus consoles, all combined on the one report.

The batch process of generating it also minimizes the real-time impact on the system during prime operating hours.

As we look at batch reporting, we should also think about external batch reporting options that provide additional opportunities to maximize our reporting capability.

As previously mentioned there are other organizations within the enterprise that can benefit from the source data that

Book 6291 I

The book also delves into the need for sophisticated audit and monitoring tools and processes to support forensic investigations.

Although many organizations today outsource the work of forensics because it may not be cost-effective to maintain the skills or the tools in-house, your systems must still provide the logging and audit trail information on the front end of the process.

A further challenge then is to not only provide the logging data, but to be able to archive the logs and actually retrieve information back from the process.

The book discusses the pitfalls and the challenges of doing this and offers some options and solutions around audit and monitoring in support of forensics.

Audit and Trace Log Management: Consolidation and Analysis provides a wealth of information and education in the form of process walkthroughs.

These include problem determination, requirements gathering, scope definition, risk assessment, compliance objectives, system design and architecture, implementation and operational challenges, product and solution evaluation, communication plans, project management challenges, and finally making the financial case or determining return on investment (ROI).

Utilizing templates, tools, and samples designed and presented to enhance the reader’s understand-ability of the process and the solution set, the author continues to build on the central and core themes of the book. He also includes many diagrams throughout his discussion aiding in a clear understanding of the process and solution recommendations.

Ultimately the readers are provided with a roadmap and a “how to” guideline leading to the successful implementation of a state-of-the-art auditing and monitoring system.

Most will want to read it from cover to cover, and also add it to their bookshelves for frequent reference.

The most value is derived from the understanding that all projects are different and all organizations change somewhere along their life cycle.

Armed with the knowledge from this book, you will be able to champion and guide your organization through a disciplined and well-defined audit and monitoring project.

It isn’t a stretch to be able to design and implement the system while fulfilling a diverse set of requirements and organizational needs.

At first glance, it would appear that the targeted audience of the book is firstly information security practitioners, but the book also has a more widespread appeal, extending to other business and functional organizations having a stake in the project’s success or having a role to play throughout the project’s life cycle.

Examples of these other organizations

include human resources, finance, system and network administrators, auditors, risk and compliance personnel, external auditors and accreditation authorities, IT architects, operational managers, and so on.

There is even value to upper management and executives making decisions and approving funding.

Each chapter builds upon the next in an organized and structured fashion providing step-by-step guidance and detailed and thorough explanations.

The author uses many illustrations, analogies, and a bit of humor as he leads us through a large and complex set of issues and challenges.

He shows us how to understand the drivers leading to the need to implement an audit and monitoring system.

At the onset he defines key drivers that are common within our regulatory and legal environment, as well as common to managing risk and security within organizations.

As a peer security practitioner also faced with this dilemma, I appreciate his understanding, knowledge, and experience leading to the realization that this is not a “one size fits all” set of solutions, steps, or phases in comparison to some other IT project such as data center consolidations.

With each chapter, the author continually demonstrates his keen knowledge of the underlying problem we are trying to solve with audit and monitoring.

It is clear that he has thought about this problem for a very long time.

He understands the well-traveled road that brings us collectively to this resource, seeking knowledge and direction for designing and implementing an audit and monitoring system within our own organizations.

Different organizations are all somewhere down the road to solutions in this arena and with this book we can basically step in at any point within the process.

It is also a good guideline to assess our own audit and monitoring systems for enhancements and improvements.

As readers, we are presented with countless options and information, as well as the tools to “put it all together” for ourselves.

This author is uniquely qualified to speak to this subject. It becomes quickly apparent that he has thought about and struggled with this problem and its resultant challenges for quite some time.

He references and discusses countless implementations that he has done over the years as he illustrates the progression of his own thoughts on the subject.

He sets out to save us from going down the wrong path in our own implementations and to enable us to benefit from his experience and gathering of knowledge.

It is further obvious that he keenly understands that there isn’t a “one size fits all” solution set for this problem, but rather, a variety of solutions, based on individual needs and requirements.

He discusses a variety of approaches and solutions that include both commercial off-the- shelf (COTS) solutions and internally developed software and solutions.

He also addresses combinations of COTS and in-house developed tools as

we now have the ability to correlate (and we should take advantage of this opportunity because rarely do security organizations have the opportunity to be a service to the organization versus a perceived burden to it!).

This is an opportunity to promote our security organization through our ability to provide value reporting outside the security group.

As we move further into this topic, we must keep in mind that it is not the charter of SOC staff to provide external reporting.

But the question remains: why not leverage the security group’s ability to provide external report value via its system reporting without adversely affecting system performance.

Knowing that external customers who receive these batch reports don’t require the same level of detail or timeliness of reports that SOC and NOC personnel require, the challenge is to be able to generate a meaningful and detailed report to the customer within a usable time-frame without overextending security resources.

Batch file reports should all deliver some degree of detail.

They should look much like what the real-time SOC staff sees, albeit received via batch process at predefined periodic intervals. In addition, given that it is for external user groups, it must be relevant enough to be of value.

If there is a need for more detailed and current information, then a request can be referred to the SOC call number for further analysis and assistance.

The batch report should have a run cap on it for size, possibly only showing the top ‘nn‘ number of events, or past ‘n’ number of hours so that it doesn’t get too large under extreme circumstances.

It should also have a set retention period (knowing the original records are preserved, this is merely a forwarded report and, therefore, the report itself wouldn’t have any set retention requirements). The only question here is how long the end users require the ability to view these reports.

Given the fact that it is a drill-down, with detailed reporting, and probably only periodically utilized, a short retention period is recommended, possibly as short as a week.

This will all be decided as a result of the user community, and more important, experience and trials of the reporting infrastructure.

A few additional considerations for retention include the size of the reports and storage capacities. Are the reports stored on a single central server or distributed across your enterprise?

A distributed approach spreads the storage load out among multiple servers, possibly making better use of resources, but also introduces additional risk of distributing security reports.

This could also potentially mean added costs to protect these reports.

If the reports are distributed to outlying hosting servers and it were deemed necessary to encrypt the reports, then multiple SSL encryption keys would have to be purchased, at least one for each distributed host server receiving and redistributing the security reports.

In some cases if the central server were sized appropriately, economies of scale in storage could make the centralized approach more cost effective.

the issue of separate user access rights lists has always been around; in addition, the linking to the common LDAP directory of users is a logical solution set that has become quite common.

The second condition may be slightly more difficult as it relies on the directory of users having the required information to be able to run a role-based access control methodology.

Hopefully this won’t be as challenging as having a directory that has user groups, as well as their placement within the company by OU (Organizational Unit) which is also a fairly common concept.

Again, this all takes up-front knowledge and planning, especially when selecting a SEM system to know to ask questions such as, “Does the security event manager allow role-based access control from an external directory structure?”

We’ve begun to cover basic reporting from SOC real-time to nonreal- time batch NOC reports delivered to non-SOC personnel. Let’s dig deeper into external reporting options.

Let’s start with one of our previous external reporting scenarios, where we reported on suspicious desktop machines that were identified in reports when correlated with eradicated viruses and potential sources of suspicious network traffic.

The report of course has security ramifications, but it may also be useful to desktop support personnel whose responsibility it is to ensure that current desktop protection software is deployed, or if a deployment effort or update failed, which led to the desktop (or groups of desktops) showing up on the SOC alert report.

The appropriate report for this group would be generated in batch mode (and if possible in a further attempt to maintain the efficient performance of your system), only run on the 72- to 120-hour basis (three to five days).

The recipients would be the desktop support group responsible for the timely distribution of the AV updates, as well as the base AV software. The fewer times a day or week that even batch reports are run, the better off the overall performance of this system.

Our desktop support team is a good example where the data is not so time critical (infected machines that have been corrected, knowing that is one of the input sources from the enterprise virus defense system that is reporting those machines it has patched) as to not demand frequent reporting.

So it soon becomes evident that this is a report that doesn’t require as timely a reporting cycle, so the “Infected machine, anomalous traffic” report could be batch run on a 72-hour cycle and reported and still provide a degree of value to the end user(s).

It will show those machines that had viruses detected as well as (through correlation with the network IDS) show a match to that machine as generating suspicious traffic.

If a pattern of the same machine or machines shows up on this report, analysis should be performed on that particular machine (or groups of machines) to determine if the update process is still working, or if it requires further degrees of protection because it continues to get infected

the issue of separate user access rights lists has always been around; in addition, the linking to the common LDAP directory of users is a logical solution set that has become quite common.

The second condition may be slightly more difficult as it relies on the directory of users having the required information to be able to run a role-based access control methodology.

Hopefully this won’t be as challenging as having a directory that has user groups, as well as their placement within the company by OU (Organizational Unit) which is also a fairly common concept.

Again, this all takes up-front knowledge and planning, especially when selecting a SEM system to know to ask questions such as, “Does the security event manager allow role-based access control from an external directory structure?”

We’ve begun to cover basic reporting from SOC real-time to nonreal- time batch NOC reports delivered to non–SOC personnel. Let’s dig deeper into external reporting options.

Let’s start with one of our previous external reporting scenarios, where we reported on suspicious desktop machines that were identified in reports when correlated with eradicated viruses and potential sources of suspicious network traffic.

The report of course has security ramifications, but it may also be useful to desktop support personnel whose responsibility it is to ensure that current desktop protection software is deployed, or if a deployment effort or update failed, which led to the desktop (or groups of desktops) showing up on the SOC alert report.

The appropriate report for this group would be generated in batch mode (and if possible in a further attempt to maintain the efficient performance of your system), only run on the 72- to 120-hour basis (three to five days).

The recipients would be the desktop support group responsible for the timely distribution of the AV updates, as well as the base AV software.

The fewer times a day or week that even batch reports are run, the better off the overall performance of this system.

Our desktop support team is a good example where the data is not so time critical (infected machines that have been corrected, knowing that is one of the input sources from the enterprise virus defense system that is reporting those machines it has patched) as to not demand frequent reporting.

So it soon becomes evident that this is a report that doesn’t require as timely a reporting cycle, so the “Infected machine, anomalous traffic” report could be batch run on a 72-hour cycle and reported and still provide a degree of value to the end user(s).

It will show those machines that had viruses detected as well as (through correlation with the network IDS) show a match to that machine as generating suspicious traffic.

If a pattern of the same machine or machines shows up on this report, analysis should be performed on that particular machine (or groups of machines) to determine if the update process is still working, or if it requires further degrees of protection because it continues to get infected.

An example of an external group that could benefit outside your core security group is your network operations group.

The fact that you could be collecting from a multitude of devices, but most important, your firewalls, both on the perimeter and internally, you will have near real-time data from these devices at a single point from across your enterprise.

This may cross product boundaries as well, such as between your Check-point and Cisco Pix firewalls; the point here is each of these has its own management console, but it is specific to its own product arena.

You have the benefit of being able to collect from both and view them side by side on a single console.

Generating reports of firewall denies and overall activity (from a security perspective) can be quite helpful to the network group by showing possible misconfiguration of other network devices or components, especially those facing the internal firewalls.

If a firewall is suddenly denying a high volume of traffic and it generates identifying records where this traffic is coming from, this could be quite useful to the network performance management group.

Events such as this may go undetected by their normal network sensors (until they reach a critical mass), but your ongoing reporting structure may provide an early warning type of alert across a heterogeneous platform of devices.

(In fact, it has been the author’s experience that the network group not only wants to see such reports, but has gone to the point of requesting real-time console access to make its own queries once it was discovered that all the log data was available in a single console access.)

This discussion further makes the case for plenty of advance planning of the overall system needs prior to diving into a purchase.

By having the whole architecture laid out in advance, including the aspect of reporting cycle, it will help in making cost-effective purchases based on estimated sizing of components such as mass storage, server encryption, user base, and systems to be managed.

A final consideration for generating any number of static reports is protection and access controls. Because the reports are static implies that they will be stored somewhere for some period of time and this scenario creates a risk factor.

If the reports were deemed valuable and included information from a multitude of security systems, they would therefore warrant adequate protection.

Protections available depend on the methodology utilized to generate the batch reports.

Many SEM products today have protection capabilities for the reasons stated previously (relieving the system of volumes of real-time ad hoc queries against the main data repository).

Because the COTS products have built-in scheduled report generation capabilities, some may also include protected output queues.

These are usually built around some form of role-based access control. This gives the report providers the ability to grant report access by user group or role-based access. In the best-case scenario, the system would–

–use enterprise access controls, such as an LDAP directory of users, potentially even using predefined user roles.

By leveraging a preexisting repository of users, logging and report administrators would not have to enter all the users into yet another directory system, with a different set of access controls and rules.

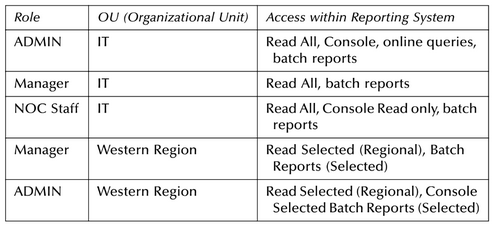

Depending on the degree of roles defined in the user directory, we may be able to grant access based on the existing roles in the manner depicted in Table 6.2.

Using this sample of roles and access rights list, it could be used to grant access (and protections) over potentially sensitive data as well as system functions.

Note how the IT ADMINS are the only ones with broad- based access not only to the reports but also the functions of the system such as uninhibited console access.

The IT managers are merely granted Read and Batch Report access (recall how we stated that the ad hoc query function on the console must be severely restricted in order to preserve system performance).

Then by further using roles such as “Regional” access, we can further restrict access not only to functions, but selected data within the reporting functions, specifically those related only to their region or area of the company.

This could be identified by keying off the actual data itself, such as some identifier for a North American firewall log versus a European firewall log, either through the naming of the device or the designated IP ranges of addresses assigned to the various regions.

If you are able to make this designation, then you could restrict the North American users to view only data associated with their device logs within their geographic region.

Our assumptions for applying these access controls rely on a couple of conditions: first, the COTS SEM product that was selected has the capability to base its access rights on an external LDAP directory and second, our LDAP directory has the same degree of “identity” (as in our sample) tied to each of the user entries. The first condition is not uncommon;

the issue of separate user access rights lists has always been around; in addition, the linking to the common LDAP directory of users is a logical solution set that has become quite common. The second condition may be slightly more difficult as it relies on the directory of users having the required information to be able to run a role-based access control meth- odology. Hopefully this won’t be as challenging as having a directory that has user groups, as well as their placement within the company by OU (Organizational Unit) which is also a fairly common concept. Again, this all takes up-front knowledge and planning, especially when selecting a SEM system to know to ask questions such as, “Does the security event manager allow role-based access control from an external directory structure?”

We’ve begun to cover basic reporting from SOC real-time to nonreal- time batch NOC reports delivered to non-SOC personnel. Let’s dig deeper into external reporting options.

Let’s start with one of our previous external reporting scenarios, where we reported on suspicious desktop machines that were identified in reports when correlated with eradicated viruses and potential sources of suspicious network traffic. The report of course has security ramifications, but it may also be useful to desktop support personnel whose responsibility it is to ensure that current desktop protection software is deployed, or if a deployment effort or update failed, which led to the desktop (or groups of desktops) showing up on the SOC alert report. The appropriate report for this group would be generated in batch mode (and if possible in a further attempt to maintain the efficient performance of your system), only run on the 72- to 120-hour basis (three to five days).

The recipients would be the desktop support group responsible for the timely distribution of the AV updates, as well as the base AV software. The fewer times a day or week that even batch reports are run, the better off the overall performance of this system. Our desktop support team is a good example where the data is not so time critical (infected machines that have been corrected, knowing that is one of the input sources from the enterprise virus defense system that is reporting those machines it has patched) as to not demand frequent reporting. So it soon becomes evident that this is a report that doesn’t require as timely a reporting cycle, so the “Infected machine, anomalous traffic” report could be batch run on a 72- hour cycle and reported and still provide a degree of value to the end user(s). It will show those machines that had viruses detected as well as (through correlation with the network IDS) show a match to that machine as generating suspicious traffic.

If a pattern of the same machine or machines shows up on this report, analysis should be performed on that particular machine (or groups of machines) to determine if the update process is still working, or if it requires further degrees of protection because it continues to get infected

and get eradications on a regular basis.

Whereas other reports (i.e., firewall failed authentications) may be more sensitive and subject to the security access controls, this type of report may not be as sensitive as some of the other batch reports that we spoke of earlier, and thus they might be able to be hosted on distributed servers, not requiring encryption or, for that matter, much in the way of access control.

This follows the old rule of applying security controls such that they are commensurate with the sensitivity of the data.

As we continue to work through various options, we must always keep in mind the importance of delivering the data and reports in a timely manner, while still providing adequate protection to the data contained in the report.

provide potentially 7 x 24 alert reporting to the NOC (which is manned on an around-the-clock basis).

Our first example, which was alerting the NOC to firewall failovers, was a fairly basic event that warranted 7 x 24 monitoring and would be of value to NOC personnel who would be responsible for monitoring general infrastructure devices on the network.

The more important concept however, is how we can transfer monitoring of our security relevant events to the 24 x 7 NOC consoles, first to share the value of information we are collecting, but also to broaden the monitoring capabilities of our enterprise, including our security-specific components via this alerting mechanism.

Let’s now look at other alert types that make sense to share with the NOC for some of the reasons previously stated.

This second alert type would identify high rates of anomalies or detection of specific targeted attacks that would warrant immediate attention or at least acknowledgment.

Network security detection systems have grown to a degree of sophistication that they can produce relevant event detection and reporting, with a higher degree of confidence over the earlier systems, meaning fewer false positives.

These systems are greatly improving and add value to the security of the infrastructure, but if we don’t have trained staff to monitor and review the detections, then the system is of little use. Event collection and the correlation system should be configured to incorporate events from the IDS or IPS (intrusion prevention system) correlated against other events collected and make relevant alerts for operations personnel who may not have the in-depth security background.

Using this approach, we can then write rules to generate NOC alerts when critical anomalies are detected and ensure we are getting some attention to these high alerts on an around-the-clock basis.

Let’s start with some basic IDS/IPS alerts where there is a very high confidence that the alert is valid. Legacy network detection systems are signature-based, where there is a known signature of a known attack loaded into the sensors such that when a certain pattern of traffic is detected on the network, an alert is generated.

The more advanced systems now not only detect and report on the traffic, but are also capable of stopping the anomalous traffic when detected, hence the intrusion “Prevention” naming convention.

Although many organizations are still more than slightly hesitant to invoke this full capability, systems are becoming more sophisticated and capable of reducing the number of false positives thus giving security managers the confidence to allow these IPSS to perform their core task as programmed.

With this confidence, our event collector can then have the confidence to report high-risk network traffic anomalies to the NOC.

Although this is not an actual rules code, this gives an idea of the alert rule that should be written to generate a NOC alert. Analysis has to be built into this rule up front because some individuals may question why we would consider an event pertaining to Slammer as relevant when all machines have been patched against it.

This is a valid question for a low number of Slammer alerts or rather events being detected, however, when the number increases high enough that it can affect traffic in any set period of time, it may be an indication of a reinfection of an unpatched machine possibly recently introduced to the network.

Two things now need to be addressed: finding the infected machine and removing it from the network.

Even though it may not be perceived to be a great risk to the rest of the enterprise, it is still producing a potentially high amount of unwanted traffic and can possibly find another equally UN-patched machine causing further impacts on the network infrastructure.

The point here is that the combination of conditions are enough to warrant an NOC level alert, knowing that we have a 7 x 24 hour monitoring system established, and that this is potentially a high-risk, high-confidence alert.

What we have done is supplemented our SOC abilities with NOC capabilities, leveraging off resources already available within the enterprise. We have taken care in only alerting those alerts that warrant attention and, hopefully, not overburdened our NOC personnel.

A final example of the type of events that should be considered for NOC reporting, is those having to do directly with data protection. With the explosive growth of regulatory factors over the corporation’s responsibility to protect the individuals’ data that they have in their possession, an equally large number of new data protection tools and approaches have emerged.

Some approaches promote data detection sensors that sniff your network lines for movement of what is classified as sensitive data and raise an alert if specified volumes of that data type exit your network.

These new tools fall into an emerging category of “data content analysis” engines.

Other approaches to enhancing data protection within the enterprise address the perceived need to encrypt all data in transit with appliance-type boxes outside your databases holding sensitive content.

Still other tools are entering the market that claim to enforce network policy by monitoring and redirecting traffic that does not match current policy (although these are still a maturing product line, but if successful should of course be closely monitored).

The point of considering the close logging and monitoring of these tools is that they all deal with your sensitive data, potentially on a real-time basis, and any failure or action of these tools could greatly affect your business processes.

Or if the tools do mature and provide the intended value, then the alerts they generate would definitely warrant action. Take, for example, the emerging data content analysis tools, which

the issue of separate user access rights lists has always been around; in addition, the linking to the common LDAP directory of users is a logical solution set that has become quite common. The second condition may be slightly more difficult as it relies on the directory of users having the required information to be able to run a role-based access control methodolgy. Hopefully this won’t be as challenging as having a directory that has user groups, as well as their placement within the company by OU (Organizational Unit) which is also a fairly common concept. Again, this all takes up-front knowledge and planning, especially when selecting a SEM system to know to ask questions such as, “Does the security event manager allow role-based access control from an external directory structure?”

We’ve begun to cover basic reporting from SOC real-time to nonreal- time batch NOC reports delivered to non-SOC personnel. Let’s dig deeper into external reporting options.

Let’s start with one of our previous external reporting scenarios, where we reported on suspicious desktop machines that were identified in reports when correlated with eradicated viruses and potential sources of suspicious network traffic. The report of course has security ramifications, but it may also be useful to desktop support personnel whose responsibility it is to ensure that current desktop protection software is deployed, or if a deployment effort or update failed, which led to the desktop (or groups of desktops) showing up on the SOC alert report. The appropriate report for this group would be generated in batch mode (and if possible in a further attempt to maintain the efficient performance of your system), only run on the 72- to 120-hour basis (three to five days).

The recipients would be the desktop support group responsible for the timely distribution of the AV updates, as well as the base AV software. The fewer times a day or week that even batch reports are run, the better off the overall performance of this system. Our desktop support team is a good example where the data is not so time critical (infected machines that have been corrected, knowing that is one of the input sources from the enterprise virus defense system that is reporting those machines it has patched) as to not demand frequent reporting. So it soon becomes evident that this is a report that doesn’t require as timely a reporting cycle, so the “Infected machine, anomalous traffic” report could be batch run on a 72- hour cycle and reported and still provide a degree of value to the end user(s). It will show those machines that had viruses detected as well as (through correlation with the network IDS) show a match to that machine as generating suspicious traffic.

If a pattern of the same machine or machines shows up on this report, analysis should be performed on that particular machine (or groups of machines) to determine if the update process is still working, or if it requires further degrees of protection because it continues to get infected

well as combinations and hybrid architectures combining a centralized and decentralized approach.

The author presents no bias with regard to the scope of the project or the ultimate solution set.

I feel that each reader will gain enough knowledge, perspective, and insight to independently implement a successful audit and monitoring management system, tailored to each organization’s unique set of requirements.

Phoebe D Gates, CISSP, CISM.

PCS ISO/Risk Manager.

Needham Bank.

Current Needham Bank [The Country Bank of Needham] Participants.

As a Peer Security practitioner;

also faced with this;

Dilemma known as;

[ StreamLined Batch Network for Elite Processors ] such as data center consolidation.